Unveiling the stigmas around mental health that are living in our data.

Words by Alex Johnstone and Pau Aleikum

Each one of us has a personal story with our mental health. We inherit some things, and other aspects are defined by the experiences we’ve lived through. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 1 in 4 people in the world will be affected by a mental or neurological disorder at some point in their lives. Despite this prevalence, many people are afraid to seek help, in part because a diagnosis can often feel like a label that comes with a huge social stigma attached.

Think of classic films like “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” or iconic characters like Norman Bates in “Psycho.” These narratives often portray individuals with mental health conditions as dangerous, unpredictable, or even monstrous. The horror genre, in particular, has a penchant for equating mental illness with malevolence, as seen in characters who reside in or escape from psychiatric hospitals only to wreak havoc. Even well-intentioned portrayals can falter, slipping into the realm of caricature rather than capturing the nuance and humanity of mental disorders. Shows like “13 Reasons Why,” despite intending to start conversations around mental health, have garnered criticism for potentially harmful depictions.

Cultured Machines

It’s important to recognise that popular culture significantly shapes these biases that are inherent in AI systems. These systems don’t watch movies or TV, but they do “learn” from the data we feed them — which includes the words, images, and ideas circulating in our media. As a result, these deeply ingrained cultural stigmas find their way into the algorithms, reinforcing and perpetuating harmful stereotypes. In our experiment, the AI-generated images were not created in a vacuum; they are a reflection of the biases present in the datasets the machine was trained on. The machine simply mirrors collective opinion, including the stigmas perpetuated by popular culture. In essence, our pop culture has been scripting the algorithms all along, making it doubly crucial for us to confront and challenge these narratives.

It was in this context that we embarked on a research experiment in partnership with Lundbeck, a pharmaceutical company specialised in brain diseases. We transformed their communications campaign into an investigation using AI to better recognise the social stigmas that exist around mental health. We prompted an image generator to produce typical scenes from daily life, with and without the presence of mental disorders, for example, a woman in a party with depression, or a teacher with schizophrenia giving a class. We could then compare and analyse the differences between the two images to identify specific presumptions about each mental disorder that are written into our shared data footprint.

What we learned

With the example of the teacher, we can observe that without the mention of mental health in the prompt, the teacher is presented as calm, and in control as he stands over his class in a dominant position. Meanwhile, the second image presents our teacher as unstable, a dazed expression across his face, and his confusion seems to be spreading to his students as if his condition were something contagious. The contrast is stark, and based on this evidence we can objectively name the stigma and affirm that people with schizophrenia are perceived as unstable, unpredictable and liable to negatively affect those around them.

We ran the same experiment with different mental health conditions such as depression and bipolar disorder, in both professional and domestic settings. Below we see the results of a prompt that described a person playing with their child, and in the second image we added that this parent had bipolar disorder. From comparing these two images we could name yet another clear stigma, namely, that people with bipolar disorder are unstable and cannot care for others. In further testing, we also observed that people with depression are seen to spread their mood to the people around them, and that they don’t make enough effort to get better.

The objective of this research was to use our critical approach towards AI to encourage reflection and conversation around mental health stigmas, and visualise an issue that all too often goes unchallenged because of its hidden nature. If we can clearly identify a stigma there is the chance to unite in combating it, and to be more aware of when we might be perpetuating the problem.

To give the viewer a sense of the kind of language that was producing these images, we asked them to also guess at which words had been used as a prompt for certain images. This also allowed them to recognise an awareness of their own latent preconceptions.

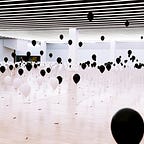

Can you guess what we might have prompted for the following image?

The simple prompt: “A man with schizophrenia cooking dinner” was enough to elicit this gruesome scenario.

After visualising the situation, it was also important for us to be able to offer our audience steps to act on this new awareness. We wanted to see how AI could help us to imagine what a more supportive and progressive perception of mental health might look like. Using these creative tools, we encouraged participants to get inspired and think up more desirable future scenarios, and ways in which we could combat prejudice together.

Can AI help to break down stigmas?

AI generated images act as a mirror to our own society and collective opinions. We are the ones feeding these machines with our ideas. This presents us with a totally groundbreaking opportunity to objectively observe stigmas we all perpetuate, without the barrier of blame and responsibility.

Labelling others with a stigma is rarely a conscious choice. From our very earliest, most simple interactions, we are being socialised to align ourselves with certain assumptions that have been built up and reaffirmed over generations. To break these collective prejudices implies a great deal of personal risk and independent will, and that means slow progress. It is incredibly difficult to take personal responsibility for culturally ingrained bias, and of course there is the fear that you will be vilified for judging others. This is where AI presents a powerful tool for us to rethink society in an objective way, without the blame that can provoke an unproductive, defensive response in many people.

At DDS we are pouring hours into critical investigation of the potential human benefits of AI. Rather than assuming the best use for this tech is to make us more efficient at what we already do, it could offer a powerful self-critique that can help us to challenge long standing problems in society and painfully-predictable cycles in human interaction. When we see bias as a feature rather than a failure of these machines, there is a sudden explosion of possible uses that could be explored.

What can we do?

The purpose of this research isn’t merely to gaze at our navels and bask in newfound self-awareness. No, we’ve got work to do. It begins with questioning your own thinking. Engage in conversations that challenge rather than confirm your views. Share resources, like articles and educational videos, that offer a counter-narrative to the stigmas we’ve internalised. And the next time you see a stigmatising portrayal of mental health in the media, don’t just roll your eyes, speak up. Your voice could be the ripple that turns into a wave of change.

AI could help us to become more inclusive, considerate and responsible as a society, especially if we can understand the potential value in reverse engineering the technology. When we assess the possibilities of this technology we cannot think of it as we typically do when we look at the latest new invention. This is not a car designed to move us around faster and more safely. Or a phone that connects us over long distances. This is a mirror, and as such it is rooted in our own identity. This is not something external, but an opportunity to learn more about ourselves through working backwards to understand why we see the reflection we do.

Why we must remain critical

We often think of artificial intelligence as this neutral entity, a digital tabula rasa that we mould with data and algorithms. But in truth, the mirror is two-sided: Just as we transfer our inherent biases onto these machine-learning models, they, in turn, reflect these biases back onto us. This isn’t merely an echo; it’s a transformation, subtly shifting our perspectives in ways we aren’t even aware of.

A recent paper by Laura Matute and Lucía Vicente highlights how biases in AI can persist in human decision-making long after the interaction with the machine has ended. We often focus on how AI is trained on biassed data, but rarely ponder on how these systems train us, shaping our decision-making processes. This gives rise to a new kind of coevolution, where humans and machines learn from each other in a loop.

One question that looms large is: can we ever break free from this cycle of bias? The democratisation of AI development might be a step in the right direction. Inviting a diverse set of developers and users to critique and perfect these systems can introduce checks and balances. But as with any societal issue, there are no easy fixes. Remember, the next time you interact with a machine-learning model, the gaze is mutual — you’re not just training it but also training you.

References:

- Saraceno, B. (2001). The WHO World Health Report 2001 on mental health. Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence, World Health Organization.

- Vicente, L., Matute, H. Humans inherit artificial intelligence biases. Sci Rep 13, 15737 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42384-8